An interesting piece in which the author examines the divide between artists (specifically problematic ones) and their work, postulating that we can accept and still consume the work of some jerks (Rowling, Michael Jackson, etc) because their terrible politics and proclivities don’t enter their work, while others (Louis CK, the Cohen brothers, etc), we can’t because their work is predicated on their terrible politics. But in the end all I think about is this: do I want my money ending up in the clutch purse of a child molester or transphobe (or their duly designated corporate heirs)? No, so I will not be spending any more money at the Rowling shop and my listening to Michael Jackson will be relegated to dentist office waiting rooms. End of story.

In real life, we increasingly expect artists to behave like the fictitious heroes they create. During interviews, I’ve been asked more and more how much of my stories are autofiction, i.e. veiled autobiography. Cancel culture (or consequence culture, as LeVar Burton recently called it) is an effort to hold people accountable for harmful actions—both artistic and personal—against the common good. In the manuscripts I read for my and my wife’s imprint Joy Revolution, it’s not just the characters that have a strong social justice bent to them—it’s also the authors themselves.

And just as artists are regarded as heroes, they’re expected to behave like angels, too.

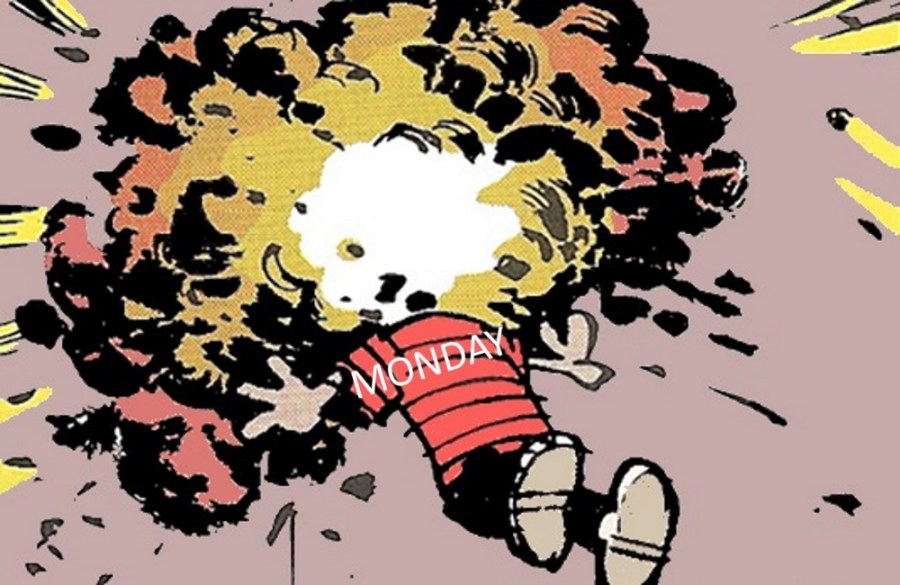

But what do you do when they turn out to be anything but angels?