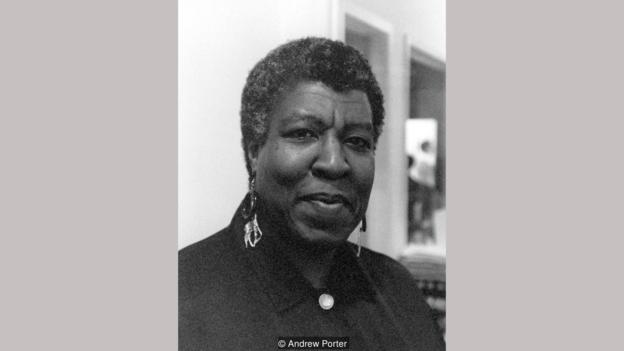

Here’s your self-isolation challenge for this week: read up on Octavia Butler and then order one of her books from a local bookstore and read it through.

Fourteen years after her early death, Butler’s reputation is soaring. Her predictions about the direction that US politics would take, and the slogan that would help speed it there, are certainly uncanny. But that wasn’t all she foresaw. She challenged traditional gender identity, telling a story about a pregnant man in Bloodchild and envisaging shape-shifting, sex-changing characters in Wild Seed. Her interest in hybridity and the adaptation of the human race, which she explored in her Xenogenesis trilogy, anticipated non-fiction works by the likes of Yuval Noah Harari. Concerns about topics including climate change and the pharmaceutical industry resonate even more powerfully now than when she wove them into her work.

And of course, by virtue of her gender and ethnicity, she was striving to smash genre assumptions about writers – and readers – so ingrained that in 1987, her publisher still insisted on putting two white women on the jacket of her novel Dawn, whose main character is black. She also helped reshape fantasy and sci-fi, bringing to them naturalism as well as characters like herself. And when she won the prestigious MacArthur ‘genius’ grant in 1995, it was a first for any science-fiction writer.