This standard author profile of English novelist Jon McGregor ends with some ruminations on the worth, use, and process of literary prizes, which gives me a chance to ramble on that for a moment.

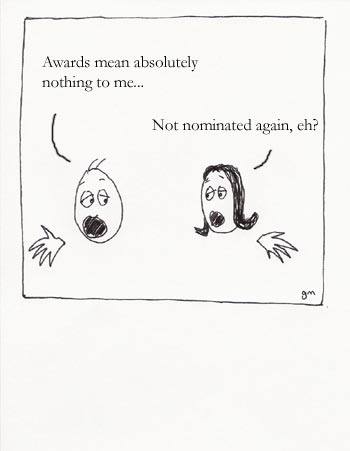

I think prizes are fine, and everyone loves to be part of them/complain about them (see illustration below), but they’re really for the industry as a whole more than any particular book. They’re about reminding people that writing is an endeavor that has artistic intent, as well as about “gamifying” the consumption of that art.

Everyone likes a winner, and award winning books boost sales so that we can all publish our not-award-winning books.

Listen, I’ve been on both sides of the prize fence and I can’t stress enough that sitting on a jury is super-difficult and in many ways super-depressing. You get boxes and boxes of books and it often just reminds you that what you’re doing isn’t special. Hundreds of others are doing it every year. And the vast majority of those efforts are actually competent. They’re fine. Okay. Not spectacular, but not bad.

Then your job is to sift through these steaming piles of mediocrity without succumbing to despair to find something that makes you care about the process again.

Oh, look, poet X has done this thing that jazzes my art-bone. Put that one aside to discuss etc. But after you’ve got your long list or shortlist as a group, well, it’s anyone’s game. The jury will jockey for position and someone will emerge on top. It almost doesn’t matter who, because the point is the shortlist and the news cycle it will generate for the industry. (I really wish people who dig award books knew this and bought the entire shortlist instead of just the winning title… usually, any one of them could have won.)

Sadly, this need for award recognition is so ingrained in the publishing process now because it’s one of the ONLY ways to break through societal indifference. In this way, it’s become both an entire subculture AND marketing strategy unto itself.

Publishers wait two weeks to a month after a book releases to see if it generates buzz and if it doesn’t, they set it on the backburner until awards season. If it gets a nomination bump then, they pick it back up and see how it does. It’s a terrible way to look at art.

That all said, publishing is a business, as is “writing” (once it’s complete). And I think there are some positives to major awards — namely the chance to write and publish more.

In many ways, a literary prize is like a 1up in a video game: the author gets a free life (some money and renown and possibly a new book deal with a hopefully bigger advance), and the publisher gets the same (more sales, notoriety, etc). In the end, it just lets us play a little longer.

Writing may be difficult, but if McGregor’s previous books are any guide, Lean Fall Stand will probably wind up on a few prize shortlists before the year’s out. (His novel Even the Dogs won the International Dublin Literary Award in 2012.) What does he think about prizes? “They mean a range of different things,” he says, then pauses for a long time, searching for diplomatic phrasing. “I think they’re both a useful way of bringing attention to hopefully interesting work, and a fairly shallow marketing trick, or both those things.”