Month: March 2020

This is a interesting piece on how a little scrap hoarding by someone back when (and I do mean scraps), has led to a “national library” from the ruins of whatever created your self-declared, still-unrecognized country in the first place. (Post only to highlight the library building, not to state anything political around it — this is still a place where homosexuality is illegal, etc.)

At the time, Somaliland was mostly trying to forget. For three years, it had been bombed into submission in a brutal civil war waged by Somalia’s government in Mogadishu. Up to 90% of its capital, Hargeisa, was destroyed. It had recently declared its independence, trying to build something new from the rubble.

But one day, Mr. Jama thought, Somaliland might want to remember.

Three decades later, the papers he gathered in 1991 have become the foundation of the library and informal national archive he is building here in Hargeisa. Like Somaliland itself, the project is a radically DIY institution, built from the bottom up with little outside help. And also like the self-declared republic, which is not recognized by a single other nation, its very existence is an act of defiance.

“This country is poor. Most of its budget must go to the basic needs of its citizens, I understand that,” says Mr. Jama in the melodic, Italian-inflected English he perfected during his years as a mathematics professor in Pisa. “But when you remove arts and culture from the equation of a society, you remove the thing that makes humans humane. I wanted to make sure that never happened here.”

- Report: digital readers are more likely to be writers than paper readers;

- I both pity and envy all the writers who have been working on, or are about to release pandemic novels;

- Academy of American Arts and Letters literature award winners;

- NBCC awards given out without glitz;

- BC and Yukon book prizes announce shortlists (go Ivan! go Sonnet!);

- Reflections on Jack Kerouac, noted Gap model, on his 98th birthday;

- More on Amazon being flooded with self-published coronavirus books (if this pandemic doesn’t teach the world some critical thinking skills, I don’t really know what will);

- A book on presidential books (Bush’s presidential book will be a (right lovable, these days) pop up, and Trump’s will be a sticky VHS tape of him getting peed on);

As pieces of information, you could copy a book as many times as you wanted, or in the case of libraries, loan it out that many times. This article labels publishers as “greedy” for limiting the number of times an e-book can be checked out at the library, but I’ll bet there’s more to it than that. I understand the point that libraries could preserve books forever, but there’s all sorts of stuff wrapped up for authors too in what constitutes “in print” vs not. My hope is that some publishing types might comment with opinions here.

But why can only one person borrow one copy of an ebook at a time? Why are the waits so damn interminable? Well, it might not surprise you at all to learn that ebook lending is controversial in certain circles: circles of people who like to make money selling ebooks. Publishers impose rules on libraries that limit how many people can check out an ebook, and for how long a library can even offer that ebook on its shelves, because free, easily available ebooks could potentially damage their bottom lines. Libraries are handcuffed by two-year ebook licenses that cost way more than you and I pay to own an ebook outright forever.

Ebooks could theoretically circulate throughout public library systems forever, preserving books that could otherwise disappear when they go out of print—after all, ebooks can’t get damaged or lost. And multiple library-goers could technically check out one ebook simultaneously if publishers allowed. But the Big Five have contracts in place that limit ebook availability with high prices—much higher than regular folks pay per ebook—and short-term licenses. The publishers don’t walk in and demand librarians hand over the ebooks or pay up, but they do just…disappear.

This is a question I struggle with every day. And not just about once-acceptable, now-problematic texts/books. People, too. At what point do you just give up and let them go. Given my somewhat strident views on things, the answer for me is largely: right away. Because as this article points out, it’s mostly not worth it. But there are a few things and people I cling to, out of love more than loyalty, that I am having a hard time with. I try to use them as negative examples, or a sort of critical thinking whetstone, to shape and sharpen my own mind and heart by looking at them with eyes wide open.

We have the privilege of living in a time where thousands of new books release every single day. It’s easier than it ever has been to gain access to good stories, the kind that don’t promote harmful stereotypes or condone or promote racism. There’s really no reason to cling to books that promote awful things – and there never was.

The classification of a harmful book though, that’s what kept tripping me up. What makes a book harmful? Does a throwaway sentence or the treatment of a minor character count? Is it anything that makes you uncomfortable when you read it? Or is there a need to read books that make you uncomfortable in order to understand those who are different from you?

- Terry Pratchett tribute by his agent (who was also his first publisher);

- Dirty laundry on the line — books about the book industry;

- That time the Dutch turned Hitler into a bug and stepped on him;

- There are worse places to be a poet than Canada… In fact, most other places are worse — Turkish poet in prison for 25 years for a crime he didn’t commit;

- Winners of the CBC writing challenge for teens — watch for these names!;

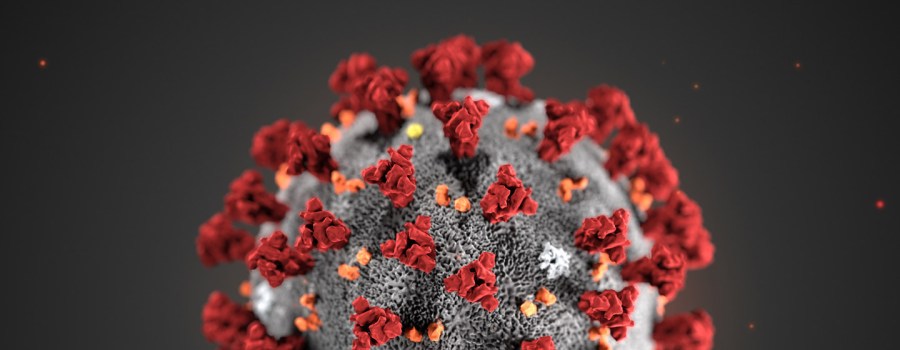

Welcome to your morning Coronavirus update. Please store this information next to yesterday’s Coronavirus update, but leave room for at least six more months of Coronavirus updates.

- Amazon cracking down on dubious virus books (now, if they could just pay their taxes…);

- Seattle bookstores are going postal;

- Chinese publishing brought to its knees by Covid-19;

- BuzzFeed posts a list of books to read if your spring break travel plans are cancelled…. (I am not fully certain that the type of people would travel for spring break are actually interested in books);

- This wee article is like a microscope on a wider problem for authors — author’s debut novel stalled by C19;

- And the same sort of thing, with a specific bookstore — can it survive?;

Decades ago, someone left a janky old cookie in the gutter of a centuries old book. If you’re still alive, you know who you are and where you’re going. Hell hath no fury like a librarian grossed out.

Well, people have started working from home and society hasn’t collapsed yet. So here are a few book related links to get you through your self-isolation. I myself don’t need to worry because I got so sick of the literary world I’ve been self-isolating for over nearly 10 years, and am skilled at getting along without seeing anyone.

- Korean ebook startup is giving 50,000 titles away for free to quarantined folk (give that marketing dude a raise);

- LAT is postponing the festival of books (you know, if things will get as bad as they say, I think the idea of “postponing” is at best overly optimistic, and at worse, a little naive);

- Even the NYPL is shutting down events in prep for the phlegmbomb of Covid-19 (it’s legal drinking age! look out!);

- Guardian offers a c19 reading list;

- Why not start in on that pile of books you’ve been meaning to read but have been kidding yourself about finding the time for until now?;

‘I think we are in a period of stagnation. New titles continue to be published into the established categories, and readers are even more prone than before to act like sheep – that is, when they read at all, they read what everybody else is reading,’ said Indyk.

Conformity in readings habits is a modern phenomenon, where one title of genre fiction dominates local and international markets. Meanwhile literary fiction, while lauded on longlists, shortlists and deemed culturally significant, does not sell. Although some titles do buck the trend and occasionally deliver excellent sales.

‘Endangered,’ that’s what Terri-ann White, Director of UWA Publishing, suggests is the state of literary fiction.