This op-ed at Bloomberg is a rallying cry for finger-the-merch set of folks who seem to have no jobs and endless hours to spend wandering bookstores. We called them Test Drivers when I worked at Coles in the 80s. Personally, while I enjoy the IDEA of browsing, I’ve never been very good at it. Ms. Ninja and our daughter The Artiste both love to just go “look at things.” My problem with that is that too often “just-looking” becomes “just-wanting” and then “just-buying.” Plus, I never have time to do browsing justice. You have to have time, wide interest, and more time. Book shopping for me has become like shopping for jeans. I want my size 36 / 32 501s (or 514s if I want to be comfy). I know exactly where they are and I beeline straight there, grab without trying on, buy, then exit as quickly as possible before someone who I had to drag along to force them off video games asks me to buy them something else. It’s a delicate, finely-tuned ritual. Book buying is like that. I go in with a list, and come out with only that list. Otherwise, the VISA starts melting. But I see his crotchety old point. So, never let it be said that I didn’t give enough time to crotchety old points.

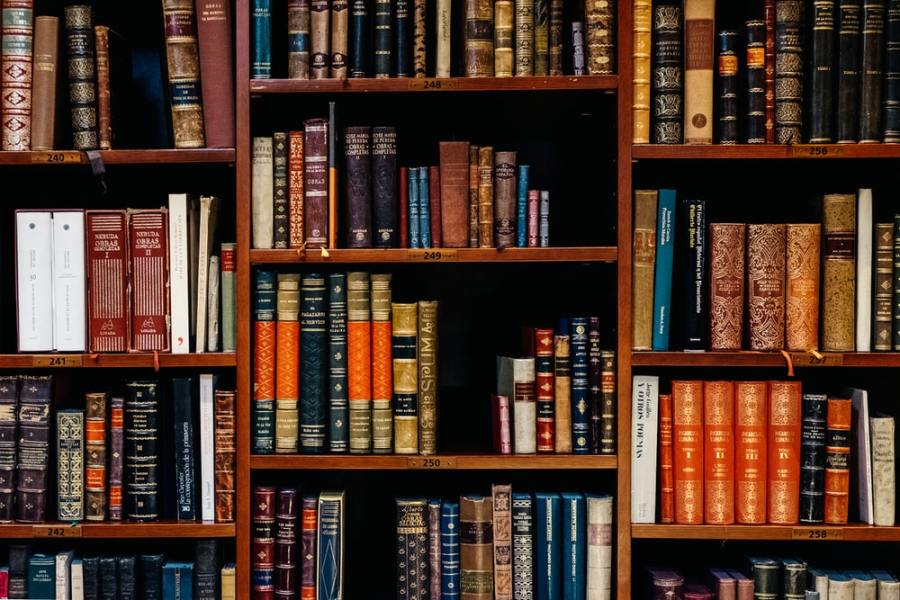

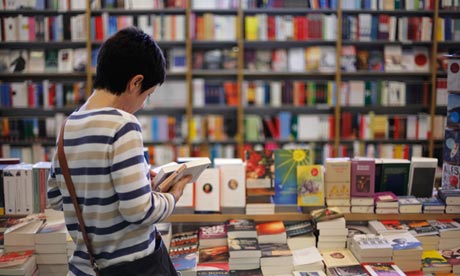

Browsing is a voyage of constant discovery. You run your fingers along the spines of the history section only to learn that the volume you’re looking for isn’t in stock. No matter. You find a fascinating book you’ve never heard of and know nothing about, a treasure upon which you happened only because you were looking for another. You pick it up, you leaf through it, you decide to buy. (Especially — no kidding! — if the smell of chocolate is in the air.) No matter how many screens you glance at online, you won’t duplicate the number and variety of volumes you can swiftly take in by spending even a few minutes in a bookstore aisle.

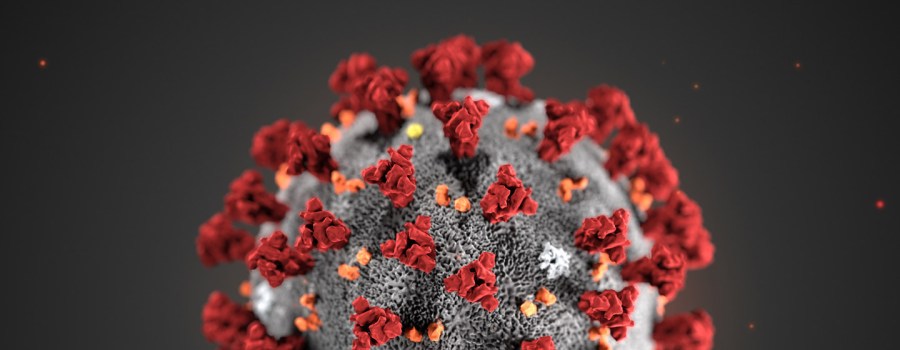

So much for all that. To begin with, a lot of people will understandably be uneasy about browsing because browsing means more time in the store, and they won’t want to chance infection by another customer. So maybe it makes sense that Barnes and Noble plans to remove those comfy chairs and benches where people used to sit and read. But browsing is also tactile, testing a book’s heft and weight even as you leaf through the pages. That’s going to be harder than ever, given that the chain has also announced plans to quarantine for five days every volume a customer handles. With booksellers nowadays often displaying only a copy or two of all but the most popular titles, the book quarantine will have many buyers ordering on their phones instead.