2020: the year of Saunders. Or if you’re Canadian, Peter Darbyshire. But I digress. The important part here is that years ago I ordered a pizza and this bedraggled dude who is obviously a grad student making extra cash shows up at the door with the debit machine and my pie, and as I’m fiddling with the machine he says, “Hey, do you know who George Saunders is?” I looked up in surprise and said, “Uh, yes, of course.” He paused a moment and said, “Are you him?” Then it was my turn to pause (and touch my forehead to feel if I had any hair at all left). Why can’t I be mistaken for Brad Pitt or something? Oh, right. The sallow, ageing redhead thing. Sigh.

We live in dystopian times. This seems undeniable as we’re locked down in a pandemic exacerbated by government ineptitude, corporate corruption and widespread disinformation. (If all that wasn’t enough, we also have murder hornets heading our way.) We should have been prepared for this after decades of dystopian works — 1984, The Hunger Games, Blade Runner, Terminator, etc. — but while these works led us to expect how dark and deadly our dystopia might be, none of them prepared us for how fundamentally dumb an American dystopia would be. Huxley can’t ready you for a reality TV president screaming in all caps on Twitter. Orwell doesn’t warn you of protesters in athleisure ware doing push-ups to demand gyms reopen during a global pandemic.

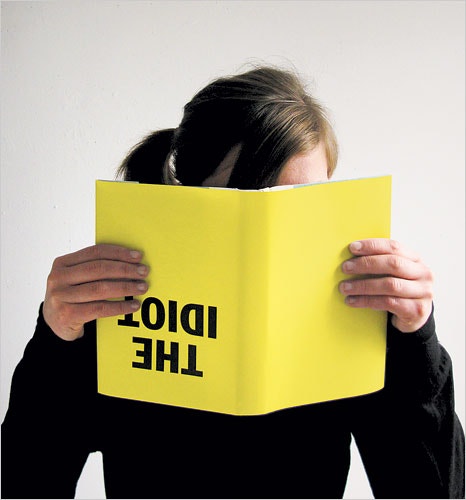

But there is one author who predicted these dumb and absurd times: George Saunders.